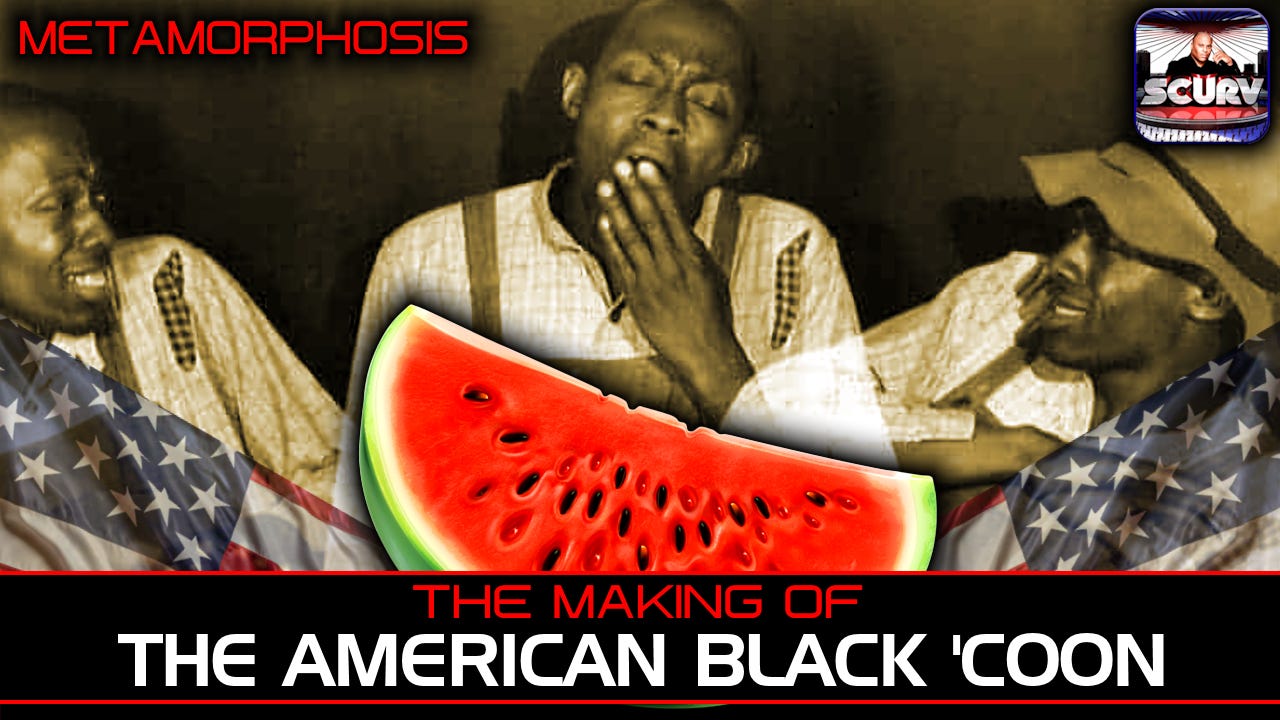

THE MAKING OF THE AMERICAN BLACK 'COON | METAMORPHOSIS

A Deeply Rooted Attack on Black Dignity

From the moment we were brought to these shores in chains, our identity has been twisted, mocked, and shaped into something we never agreed to be. This article, The Making of the American Black Coon, is not about jokes. It’s not about entertainment. It’s about exposing one of the darkest, most humiliating attacks on our spirit as Black people in America. And it was done through images, movies, cartoons, and the media. This was psychological warfare. A silent, but deadly assault on how we saw ourselves—and how the world came to see us.

Most of us have heard the word “coon.” Some think it’s just an old racial slur. But it’s deeper than that. It became a performance. A role we were pushed into playing—on stage, in Hollywood, in real life. It meant being silly, dancing, acting stupid, shuffling and smiling for the comfort of white folks. And for a long time, some of us thought playing that role would help us survive. But it came at a price: our self-respect.

This article is not here to sugarcoat or dodge the truth. This is not about pleasing anyone. It’s about breaking down how this image was created, forced on us, and even passed down through generations. It’s about putting the whole ugly truth out there so that we can understand what was done to us—and why some still play these roles today, knowingly or not.

You’re going to see names like Stepin Fetchit and Amos ‘n’ Andy. You’ll learn how advertising companies used our exaggerated features to sell soap and pancakes. How blackface performers danced and laughed while the world watched and laughed at us. How stereotypes like watermelon and fried chicken were used to label us as lazy, dumb, and satisfied with little. It was never innocent. It was strategic.

So buckle up. This ain’t about making folks feel comfortable. This is about truth-telling. If we’re ever going to rise, we need to know how far we’ve been pushed down. The Making of the American Black Coon is a history that needs to be faced—no matter how painful.

The Birth of the “Coon” Character

The term “coon” dates back to the 1800s. It was first used as an insult toward Black people, but it soon became more than just a slur—it became a full-blown character in the American imagination. The “coon” was lazy, dumb, happy-go-lucky, and always ready to make white folks laugh. He had no shame. No pride. No intelligence. Just a grin and a dance.

Minstrel shows in the 19th century made this image famous. White actors would put on blackface—dark makeup, big red lips, wooly wigs—and act like fools. They would shuffle, tap dance, and say “yes suh” and “no suh” to mimic the way enslaved Black people were forced to speak. These shows were popular all across the country. They planted seeds of racism deep in the minds of white audiences—and even in Black ones.

These characters told white America: “See? Black people are fine with how they’re treated. They’re happy, they’re silly, they’re not even smart enough to rebel.” That was the purpose. To erase the pain of slavery and present us as simple, carefree, and beneath everyone else.

This image didn’t stay on stage. It leaked into newspapers, magazines, books, and later, film and television. And it stayed there for generations.

Stepin Fetchit: The First Black Movie Star—and the Most Dangerous

Lincoln Perry, better known by his stage name Stepin Fetchit, was the first Black man to become a millionaire in Hollywood. But how did he get there? By playing the slow-talking, lazy, confused “coon” on screen. He built his fame by leaning hard into the stereotype—so hard that even white folks started calling other Black people “Stepin Fetchit” if they acted the same way.

He played the fool, but he wasn’t stupid. Perry knew exactly what he was doing. He once said, “You had to play the game to stay in the game.” And while he got rich, Black America paid the price. The white world saw him and thought that’s what all Black people are like. And some of us saw him and thought maybe that’s what we’re supposed to be.

Stepin Fetchit was not alone. Other Black actors followed the same path, not always by choice. There weren’t many roles in Hollywood. If you wanted to work, you had to play the part they gave you. And that part was usually humiliating.

The Blackface Legacy and Coon Caricatures in Advertising

Blackface didn’t end with the minstrel shows. It moved into film, TV, and advertisements. Companies like Aunt Jemima, Cream of Wheat, and Gold Dust Washing Powder used smiling, wide-eyed Black faces with exaggerated lips to sell products. These were not just drawings. They were weapons. They taught people that Black folks were meant to serve, clean, and smile while doing it.

These images burned themselves into the national mind. And children—Black and white—grew up seeing them over and over. The damage was deep. These weren’t just jokes—they were tools of oppression. They taught white people to laugh at us. And worse, they taught some Black people to laugh at themselves.

Let’s not forget cartoons like Looney Tunes and early Disney films. Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse both wore blackface in old episodes. There were characters called “Mammy,” “Sambo,” and “Rastus” that showed Black people as dumb, loud, and unworthy of respect.

The Chicken, the Watermelon, and the Lies

Let’s talk about the food stereotypes. “All Black people love watermelon and fried chicken”—we’ve all heard that. But where did it come from?

After slavery ended, many Black folks grew watermelon as a way to support themselves. It was healthy, easy to grow, and profitable. But white America turned it into a joke. Political cartoons from the late 1800s and early 1900s showed Black people sitting around lazily, eating watermelon and grinning. It was meant to show that we were happy with crumbs. That we didn’t want success or respect—just food and foolishness.

Same with fried chicken. It became a running gag. Even today, when someone sees a Black person eating chicken, they laugh. Why? Because the media told them that’s what we do. These jokes are not just harmless. They stick. And they shape how people see us—and how we see ourselves.

The Long-Term Psychological Damage

When you're constantly told you’re a joke, you start to believe it. That’s what happened to generations of Black people. This wasn’t just racism. It was mental warfare. They weren’t just laughing at us—they were teaching us to hate ourselves. To lower our standards. To entertain instead of lead. To perform instead of build.

And some of us still carry that. You see it in certain comedians. In viral videos. In reality shows. In some rappers who play the fool just to get attention. That old role of the “coon” still shows up—it just looks different now. It’s louder, flashier, digital. But the message is the same: dance, grin, and be a fool for the spotlight.

We need to break that chain. We need to teach our children that they are not jokes. That their worth is not tied to how well they perform for others. That our culture is deeper than memes and minstrel shows.

We didn’t choose to be mocked. We didn’t ask to be turned into cartoons. But they did it anyway. And for too long, we stayed silent. We laughed with them. Or we stayed quiet out of fear. But that ends now. Because truth has a way of rising—even when buried deep.

The “coon” was a lie created to kill the Black spirit without laying a hand on the body. It was a mask forced onto us—and passed down. But we can tear that mask off today. We can expose it for what it is: a sick fantasy made by sick minds who feared our power, our dignity, and our brilliance.

We are not clowns. We are not simple-minded. We are not here to entertain anyone but ourselves. We are thinkers. Builders. Creators. Warriors. Survivors. And if anyone tells you different, they’ve bought into the same lie that was sold over a century ago.

This isn’t about canceling old cartoons or tearing down statues. It’s about knowing what was done, how it was done, and why. It’s about breaking generational curses that started with minstrel shows and still show up on social media today.

The legacy of the American Black Coon is a heavy one. But we don’t have to carry it anymore. We have the power to define ourselves. To honor our ancestors. And to build a new image—one based on truth, pride, and power.

Let these words be a spark. A mirror. A warning. And most of all, a call to rise.

So many collabs that make sense and have historical proof.